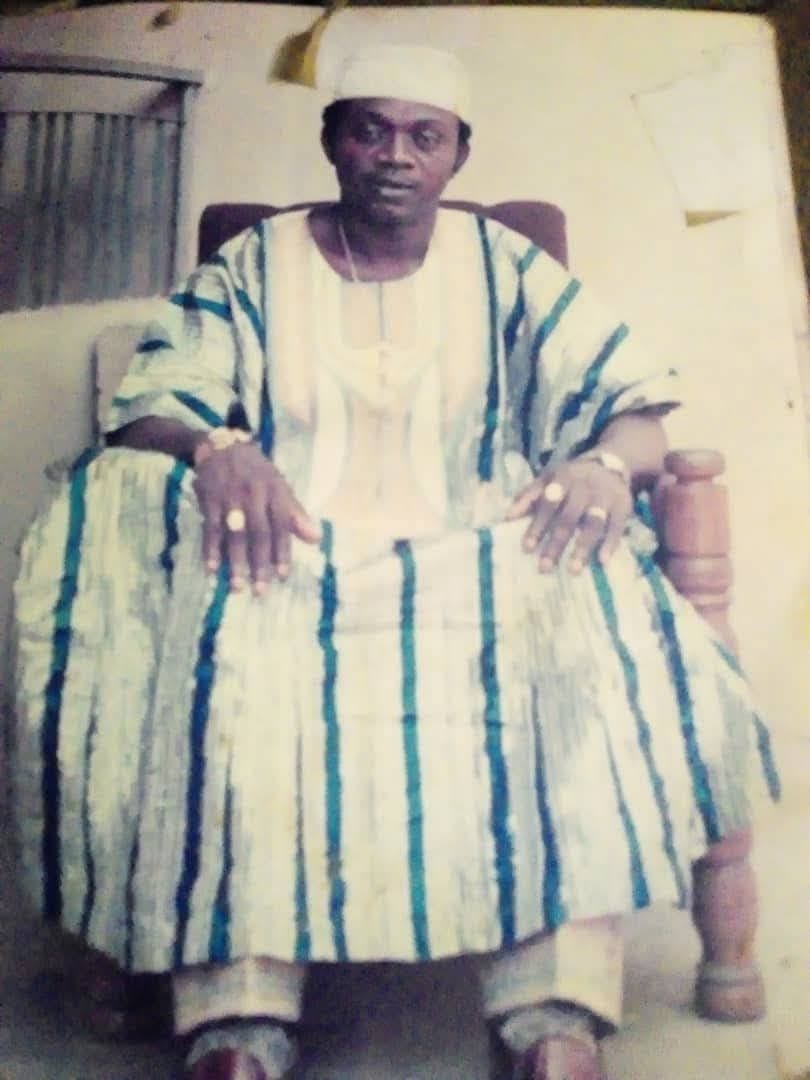

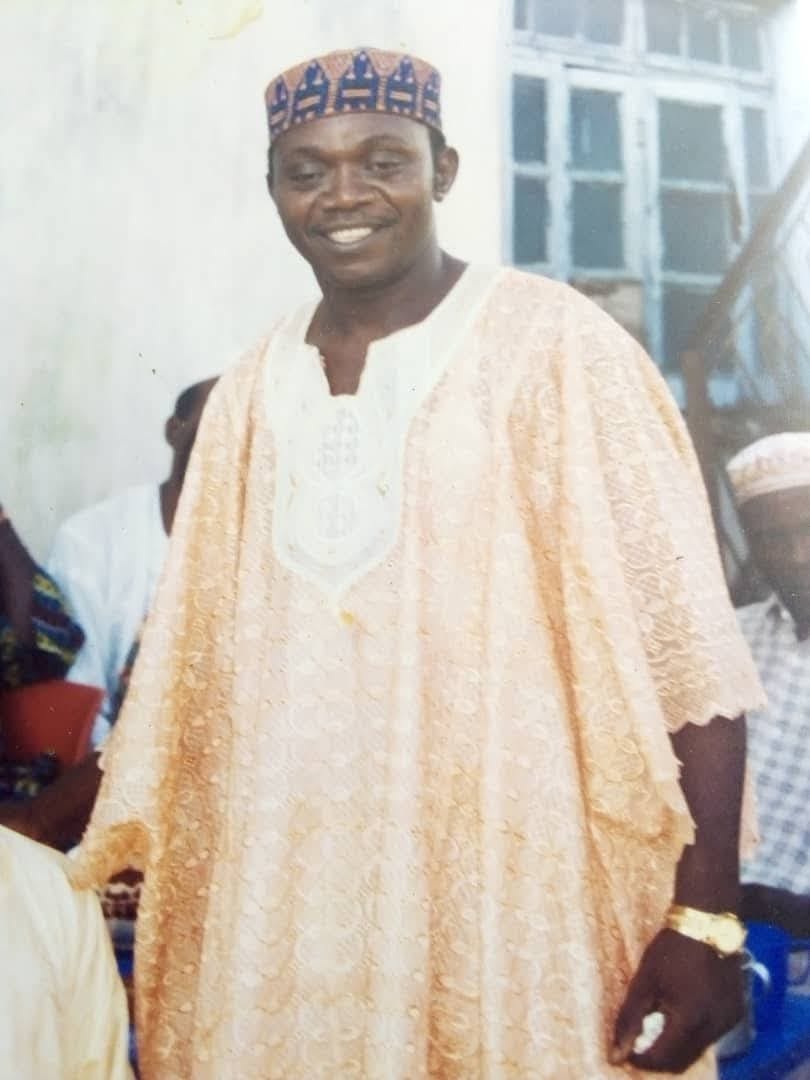

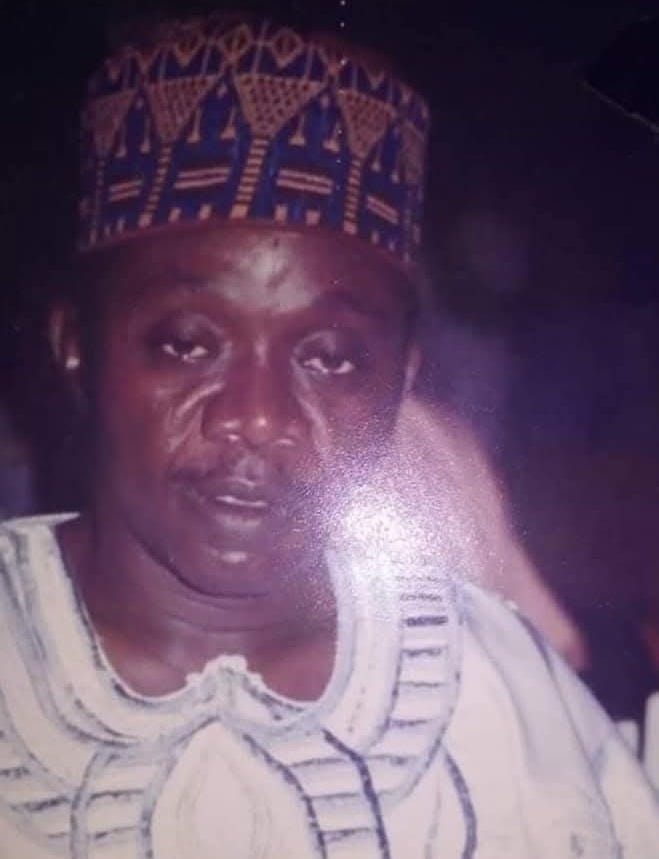

It’s five (5) years today—31st of May, 2025—since my father's demise.

I’ve published a chapbook of the poems I wrote in grief over his passing. I title the book “Some Stars Do Not Fall.” The poems helped me heal. Maybe there is truly something called fortitude. But it still aches to think about him—his struggle, his dreams, his wishes.

Most times, I feel life wasn’t fair to him. Fate is a bastard. But belief says accepting it is a part of faith.

When I was just beginning, when I was almost ready to return his care, death took him. Death could’ve allowed him just one more year, and I’d have been able to repay his kindness.

Omoh! I didn’t do anything. I was just a student all my life with him. Damn!

Here's what you’ll read:

•I live a part of my life for him

•Father allowed me to be soft

•I was a student all my life with him

• Fate is a disappointment to wishes

• Five poems from ‘Some Stars Do Not Fall

• I live a part of my life for him

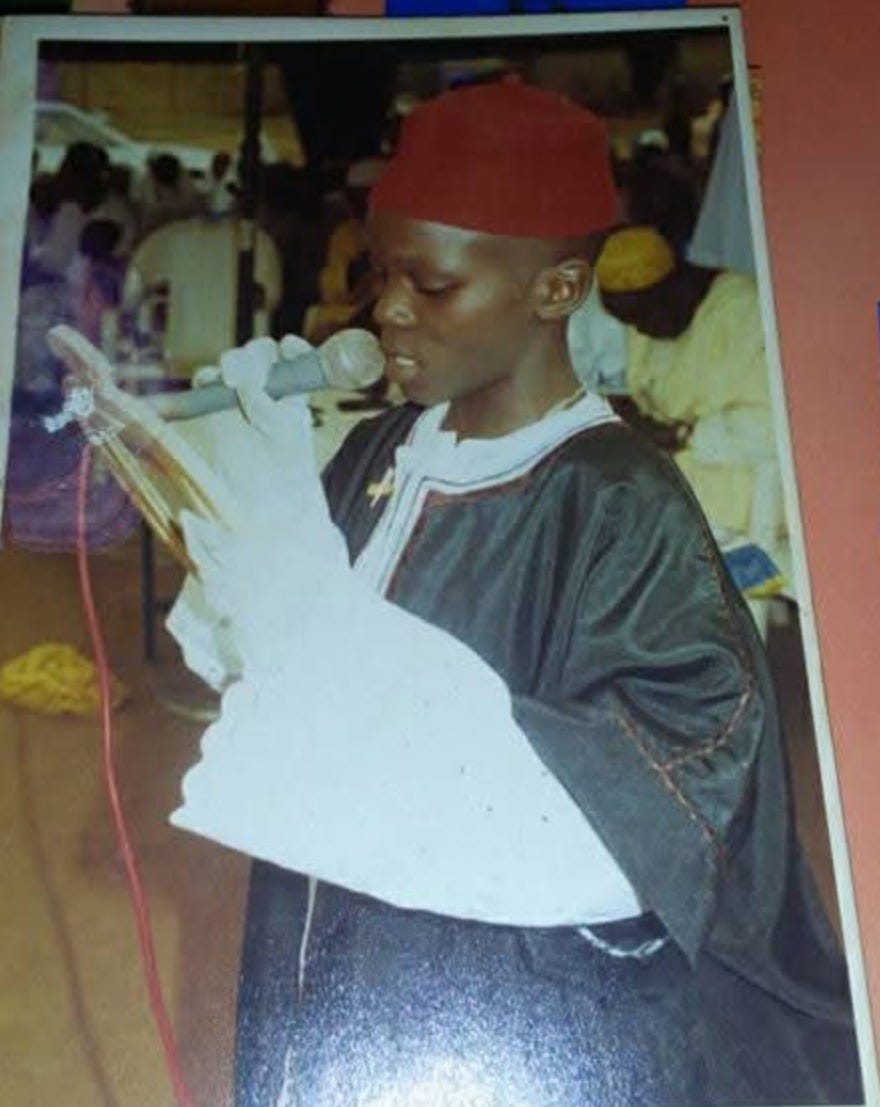

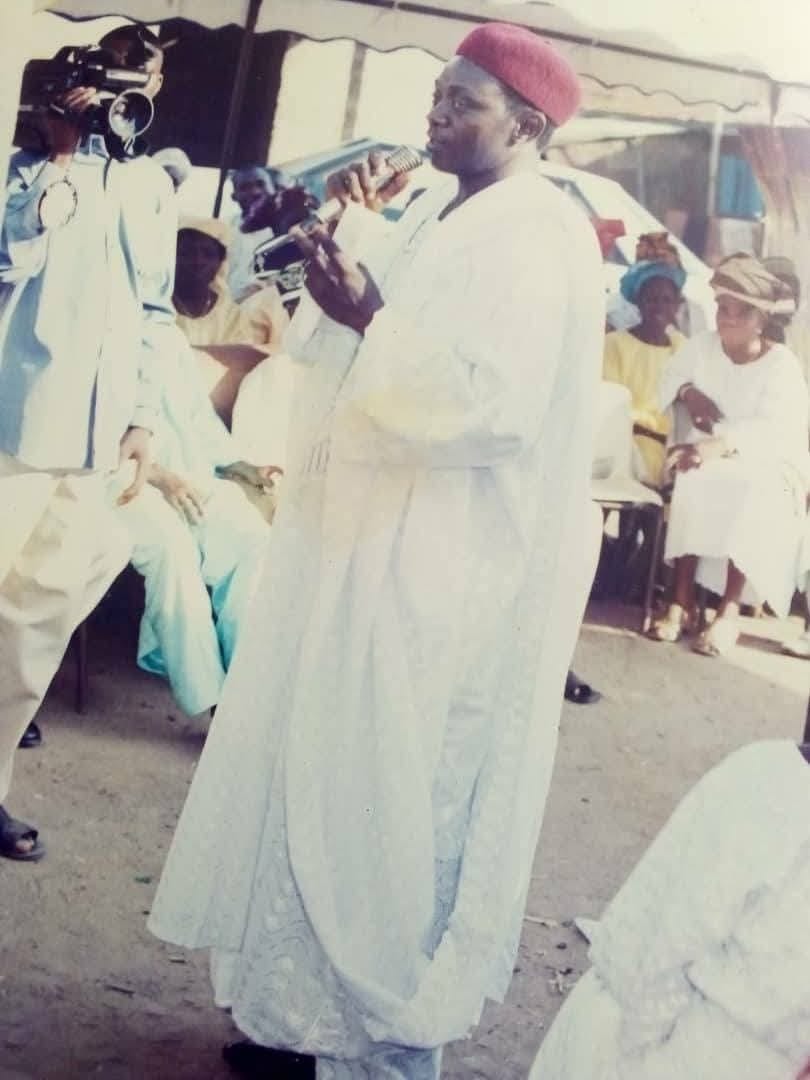

I often tell people who are close to me that my devotion to Arabic and Islam, or say Da’wah, was my way of telling Dad: “I’m living your dream.” And that truly gave him joy.

Anytime I shared my exploits with him, or he heard about them from someone else, he would bask in their afterglow endlessly. But I still think it wasn’t enough.

Oftentimes, I’d bring him and Mum news of people bearing gifts for me, and shared with them. But again, it never felt like enough. This goes as far back as 2010.

I started “giving back” in 2004 when I did my Walimatul Qur’an. I came home with ₦3,000. Took ₦1,000 for myself, gave Dad and Mum ₦500 each, and split the remaining ₦1,000 among my siblings. But obviously, that wasn’t a real thing yet.

In 2010, I travelled to Ogombo in Eti Osa to give daily lectures throughout Ramadan. Yeah, you guessed right—I was still very young, barely 20. I came back with bagloads of gifts and money. I gave Dad and Mum equally of whatever I brought (Sorry, I'm a rebellion of the 3-1 Sunnah for mother-father). But sincerely, it still wasn’t what I really wanted.

Before 2010, during Ramadan, I had been going from family to family for lectures across various streets in Sango Otta and Iyesi Otta. And during those times, before gaining admission to the University, I did my Haflatu Idadiyah (popularly called the “second walimah”).

When I got to University, Dad would always remind me not to forget the Qur’anic path. So I’d share videos of my activities with him—from MSSN (Muslim Students Society of Nigeria), to TIMSAN (Tijaniyah Muslim Students Association of Nigeria), NAMLAS (National Association of Muslim Law Students), even JAMNAS (Jam’iyyat NasruLah al-Mubeen Society of Nigeria)—the society that took me to Ogombo.

I’d share with him my recitations of Diwan at Islamic events. I’d show him video clips or play voicenotes of my poetry renditions. And if you looked into Dad’s eyes, you’d see crystals of bliss sparkling. Because—why not—I was (and still am) living his dream.

Na me wan be lawyer. Friends, Alfa (Islamic scholar/cleric) is what he wanted me to be, while supporting my own ‘lawyer’ dream. And writing is a gift from God.

And it was never about the once-in-a-while gifts I came home with from my performance at Islamic events. I was just being a good boy who thought: “When I become bigger, I’ll do bigger things for them.” It was about this for him: Father served Alfas due to his love for them and the religion, and wanted his own child to be one, too. And I lived and still am living that “Alfa” life for him.

I give public lectures, deliver Eid and Jumat sermons, and sometimes will interpret sermons for my Ustaz. I'm often been invited for Diwan / Dhikr rendition. It's important to state that more than being a joyful experience for Dad, they are all for me acts of worship and service to Allah.

• Father allowed me to be soft

Deep down, I wanted to become a lawyer. I wanted to grow and have enough to care for him the way he cared for me.

What did he do?

Father allowed me to be soft. He never said: “Be strong, you’re a boy.” Instead, he would dive into my problems and experience them with me.

Once, I got 9/10 in a classwork in Nursery 3. I told my teacher, Mrs. Owolabi, I deserved 10/10, but she insisted 9 was correct. I got home and told Dad. The next day, he followed me to school. Mrs. Owolabi checked again and apologized. She corrected it to 10/10.

Another time in Secondary School, I was wrongly accused of not paying my school fees. A teacher said, “These kids, they spend their fees on frivolities.” I got home and told Dad. The next day, he came with me and told them: “I trust my son. He doesn’t lie to me. All I need is to ask him once, and I never have to ask again. I’ll defend his truth to my last breath.” The teacher checked the records and realized I had paid. She apologized.

Once, a relative who lived with us accused me of stealing her money. I cried until Dad got back. He didn’t even ask me any questions. He went straight to her: “Never say such about my son again.”

I was the only one who had the key to my parents’ cupboard. Once, Mum couldn’t find her mint ₦5 notes and suspected me. I wept bitterly that she didn’t trust me. I knew Dad would never have doubted. Later, she found the money in a bag she had used. She apologized. I returned the cupboard key to Dad and asked him to hand it back to mum. I instead requested the key to the TV console’s drawer to keep my own things. And he gave it.

•I was a student all my life with him

I didn’t do anything for Dad as much as I had wanted. I was a student all my life with him.

Sometimes when I returned from school and offered him money, he’d refuse, saying: “You’re still a student.” I’d insist it didn’t matter, but he wouldn’t accept it. So I’d hide the money in one of his worn caps, so he’d find it the next morning.

Father aged. He was sick for a long time. He was once even declared dead at the hospital, but I kept hitting his chest and he coughed back to life.

When he got better, he couldn’t work anymore. He relied on what Mum gave (thank you, Mum, for helping him hold on), some kind relatives, and some of my siblings. The rents from his two houses also helped a bit. I understood his status, and that’s why I would offer to gift him money even as a University student. Mum and my half-brother paid my school fees. My guardian and Ustaz—who gave me all the Ramadan lecture platforms—often support my feeding, while art and writing helped me hold body and soul together, among other hustles.

During my NYSC, I came home one Ileya and gave him money again. He didn’t want to take it until I explained that I was already working and the government gave us monthly allawee. Then he collected it—but not all. So, as usual, I hid the rest in one of his caps.

Whenever I came home, I’d clip father’s nails, cut his hair, shave him. We’d gist and talk about his dreams. His house in Abeokuta has a mosque; he wanted the one in Ifọ to have one too. But where was the money?

He used to lament, with deep pain, that he couldn’t assist with my University education. And I’d tell him, “When you had, you did your best.” But he still wanted to do something. Everything he couldn’t do for his kids when his finances got bad, he still dreamed of doing in other ways. He dreamed of getting some big money, then call us and share it among us. He even considered selling part of the house in Ifọ to build the mosque and share the proceeds with his kids.

• fate is a disappointment to wishes

After NYSC, I was retained at my law firm in PH. Ironically, I was sending more money home as a Corper than when I started working. Moving back home didn't make sense to me until when I thought it would reunite me with Dad. And I started speeding up things.

And this was my plan: to secure a job back home before the 2020 Ileya festival that was already approaching, visit Dad fortnightly, bring him gifts, do his laundry, and cut his hair and nails—as usual.

I contacted lawyers in Abeokuta and got a job offer. I planned to leave Port Harcourt for good when I go home for Ileya and resume in the new office.

Dad’s phone was bad, so I always called him through Mum’s. I even had a new phone I intended to gift him when I got home. He had briefly fallen ill again. And I sent money for meds.

On the morning of 31st May, 2020—he had already gotten better and was stronger again—I asked to speak with him. I hadn’t heard from him in two days. I was told he was sleeping. At around 12pm, my half-brother got a call from home, and he looked me in the eyes and said: “Alfa. Daddy is dead.”

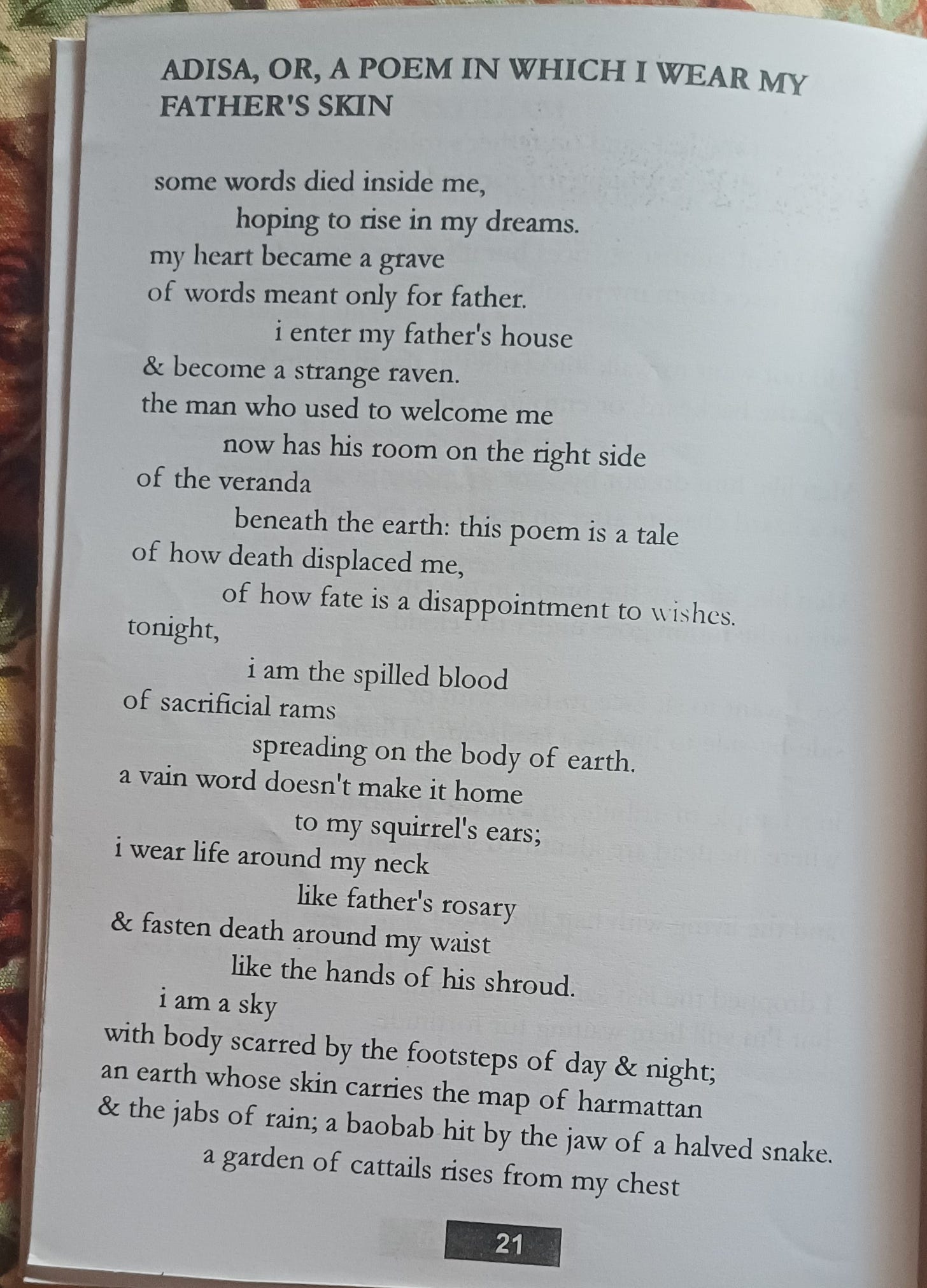

I was shattered. I felt disappointed. I felt unfulfilled, even embarrassed. And this was the reason behind the line in my poem “Adisa, or a Poem in Which I wear My father's skin” which reads: this poem is a tale / of how death displaced me, / of how fate is a disappointment to wishes. And it was my first grief poem upon his death.

When we last spoke, I had promised I’d be home for Ileya. I told him I’d now be working nearby and would be visiting regularly. Port Harcourt had always been a journey—I should’ve prayed qasr all those two years.

I didn’t do anything for Dad. I was just a student all my life with him. But I gave him joy—what must have even extended his lifetime to that time.

• Five Poems From ‘Some Stars Do Not Fall’

I’ll leave you with these five (5) poems from my chapbook. I hope they tell you deeper stories than I have here.

ADISA, OR A POEM IN WHICH I WEAR MY FATHER’S SKIN

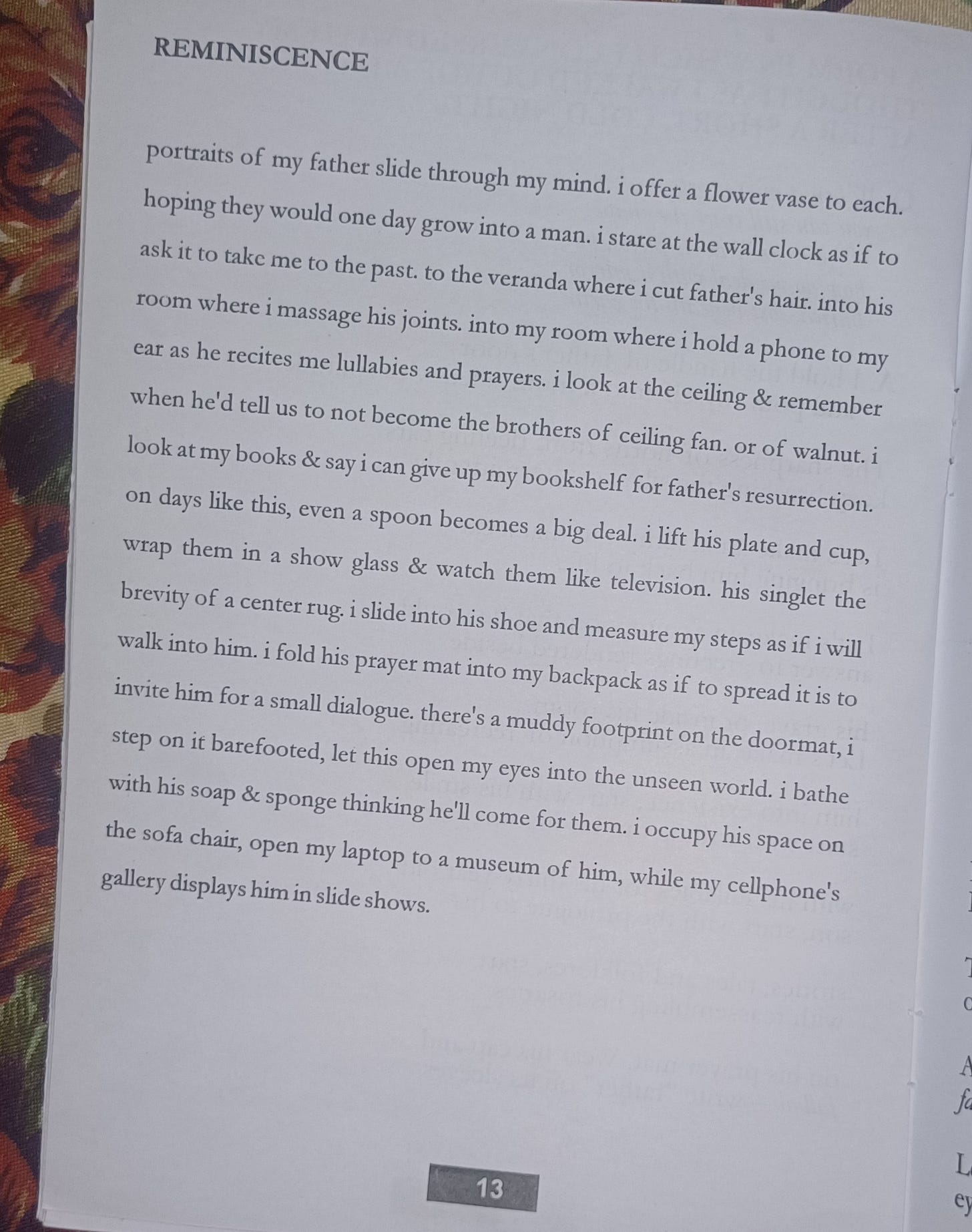

REMINISCENCE

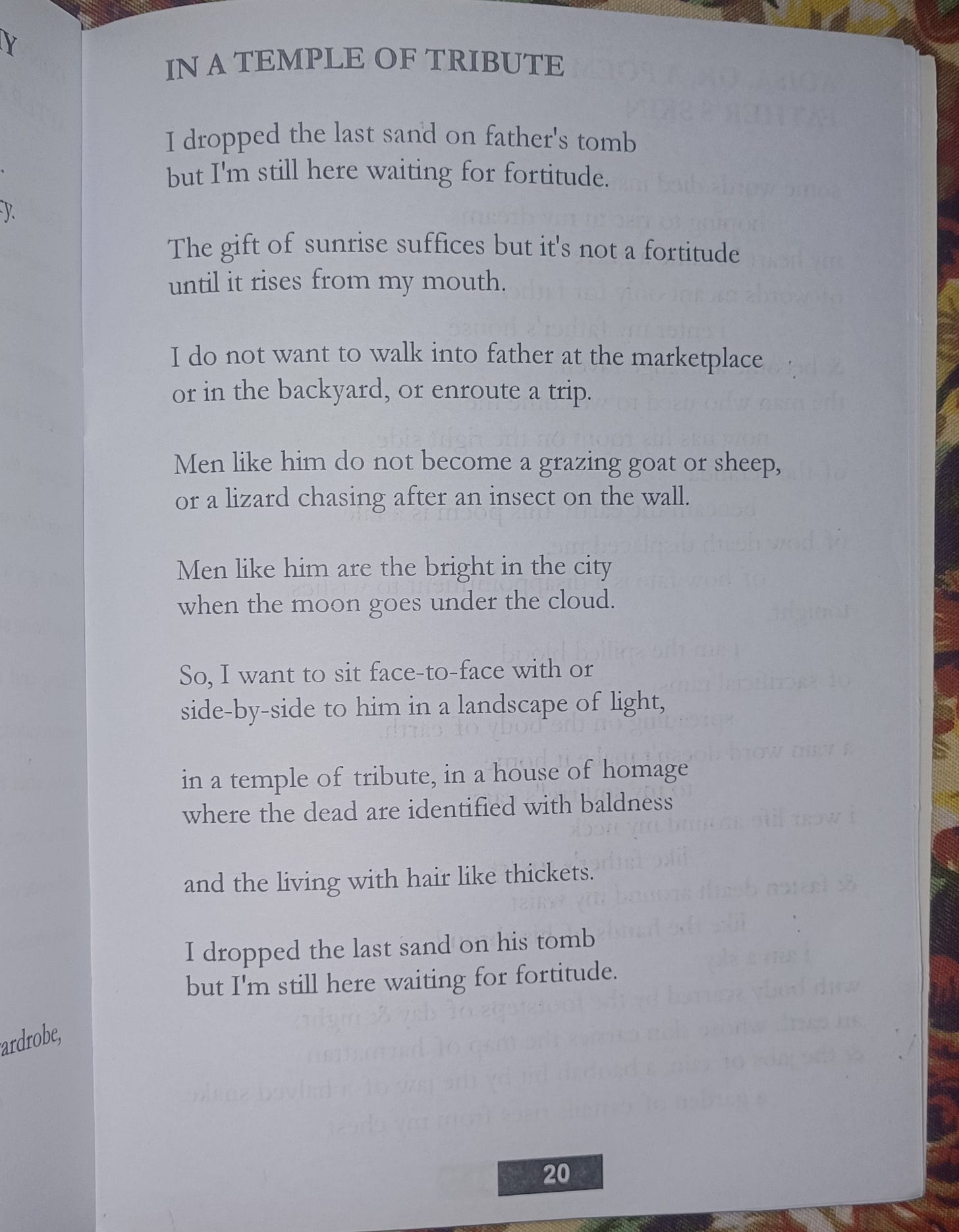

IN A TEMPLE OF TRIBUTE

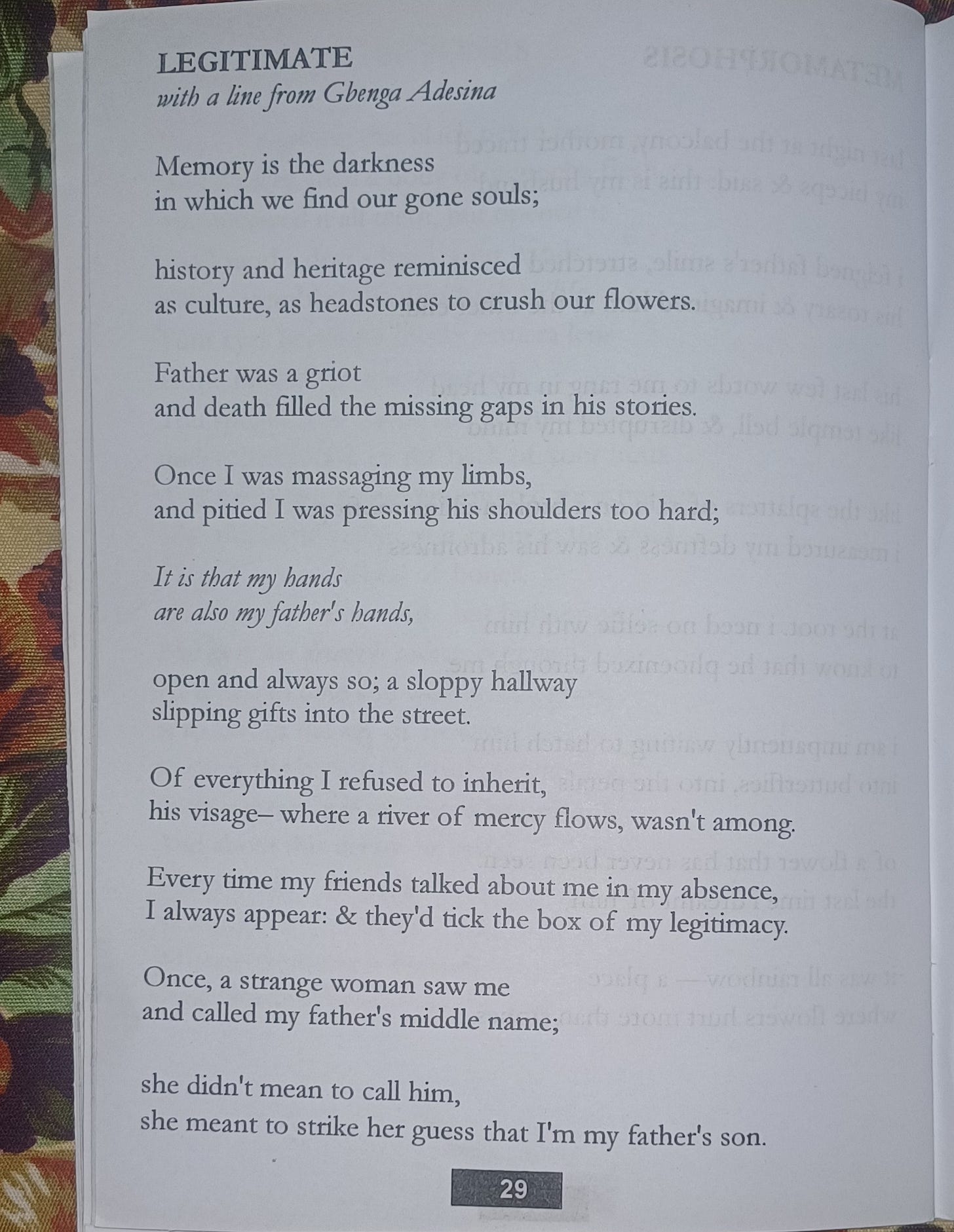

LEGITIMATE

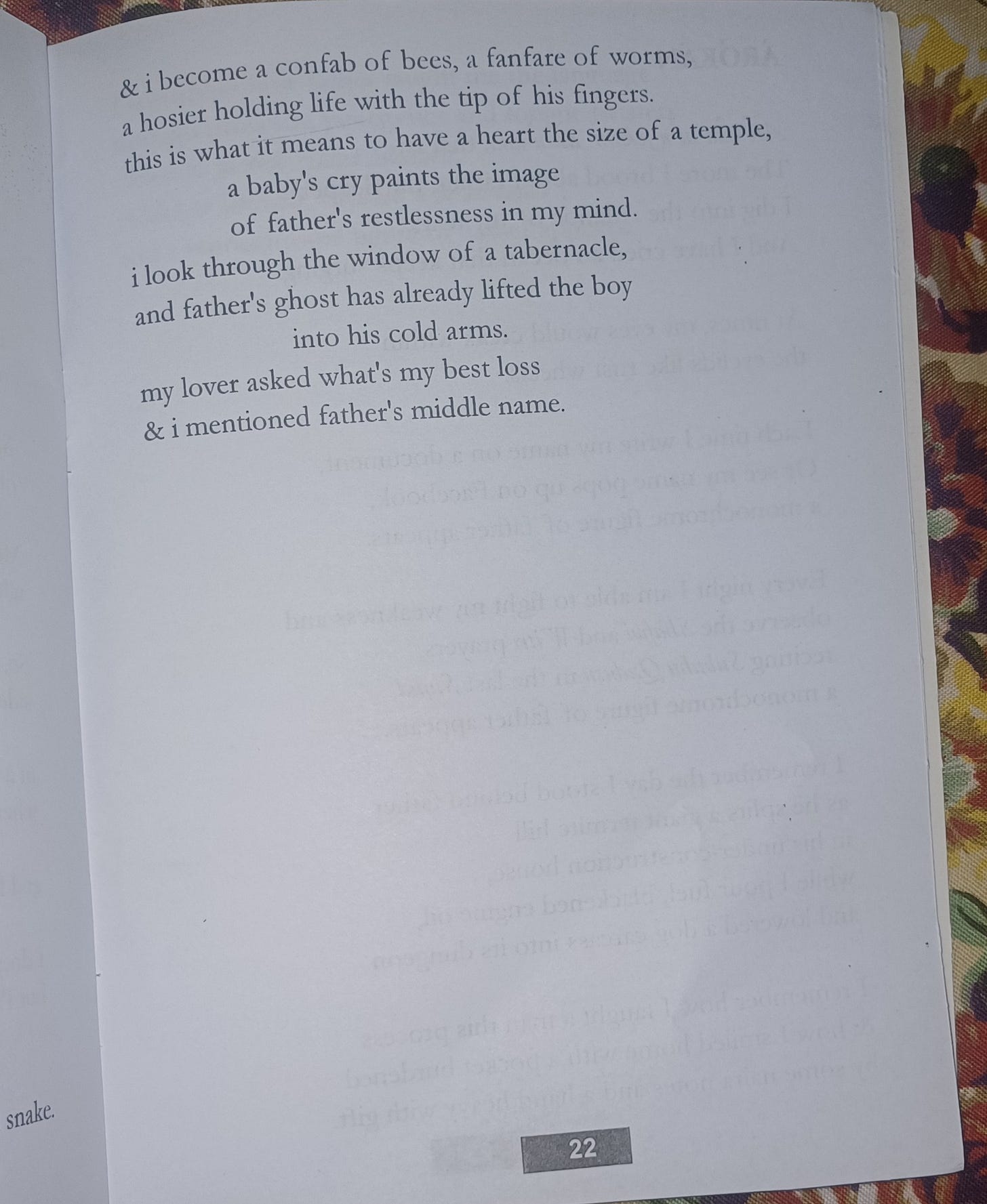

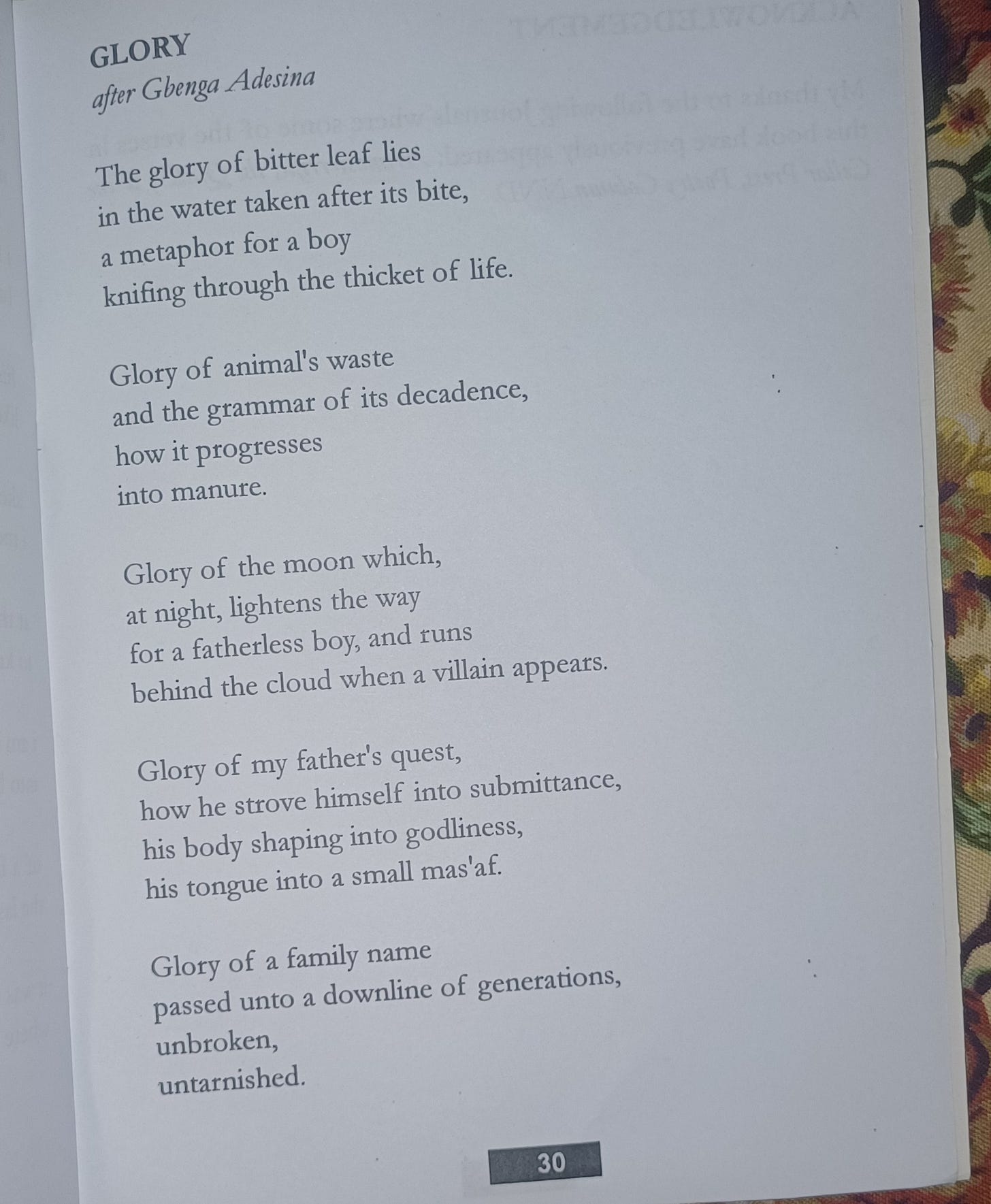

GLORY

If you'd love to get a copy or more of the book, send me an email at taofeekayeyemi@gmail.com or text me on WhatsApp via +2347035513533.

Right now, please do me a favour—say a prayer for my father. And thank you so much for that.

You can send wishes, prayers, remarks, and condolences in the comment box.

Thank you 🤝

This made me shed a tear. I read the story as if I were living your life. And it kinda reminds me of my beloved mum who couldn't wait to eat from the pot of deliciousness she had used all her life to cook. How I wished she could have waited a year more. But Allah knows best 👌.

May Allah grant all our deceased Al-Jannah and may He forgive all their shortcomings.

May Allah grant him Aljannah. You have been strong, but still be strong, sir.